Invisible Wounds

“We met in college. Mark had long hair and a beard. He was class president so there were posters of him hanging up around campus. He was really cool. I was kind of ‘not cool.’ I played saxophone in the band. I was a Christian. Neither of those things was very cool in the 70’s. I tried to impress Mark by participating in a blood drive that he was organizing. I ended up passing out and they had to wheel me out in front of the rest of the students. But we started dating eventually. Everything happened so fast after that. We got married when we were twenty-one. When he proposed, Mark told me: ‘I just want you to know that I probably won’t live long.’ His father had died of a heart attack at the age of thirty-one, so Mark was convinced that he'd die young too. Neither of us ever dreamed it was our boys we would lose.”

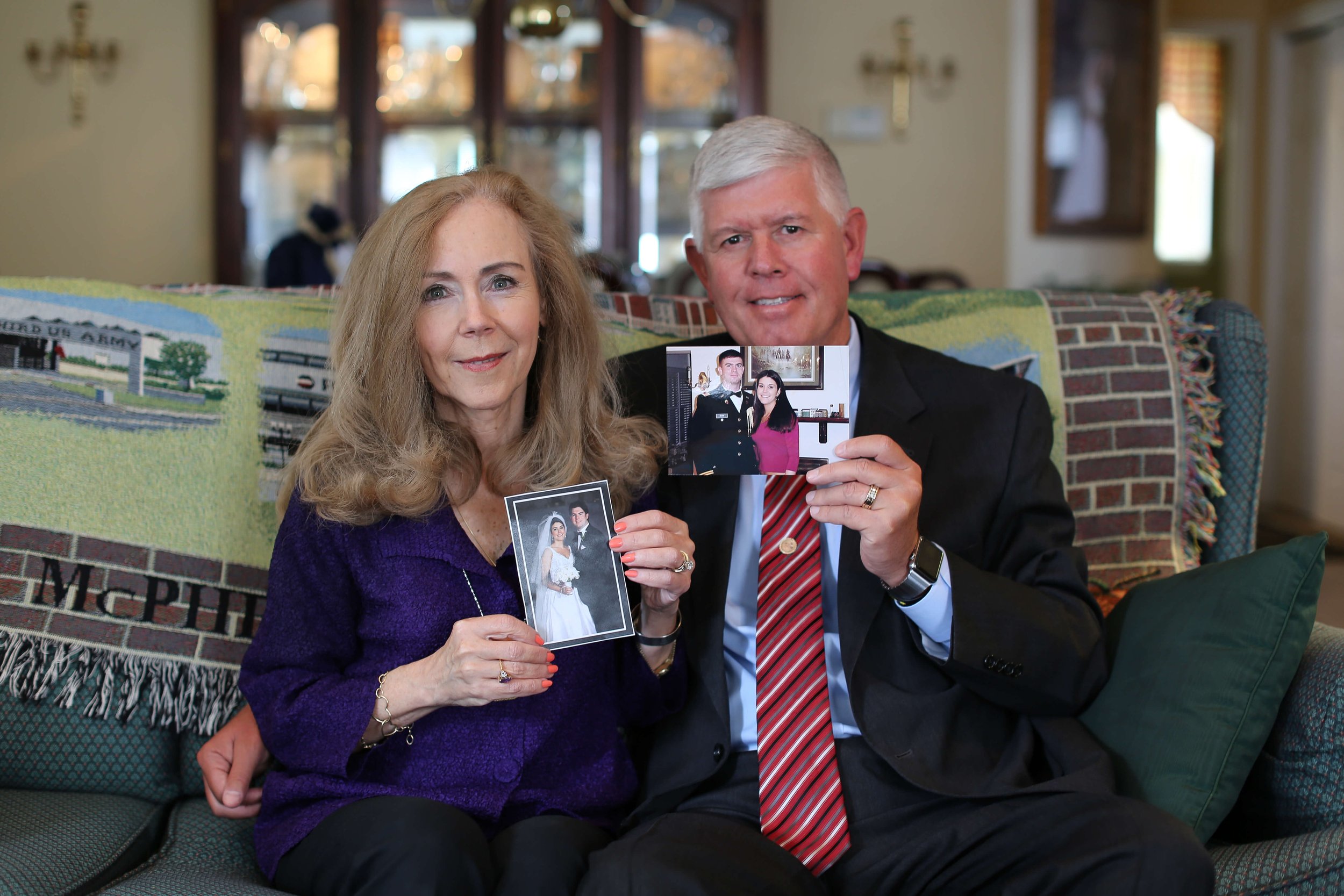

“The Army was different back then. You have to remember, we had all those years of peace. For us it was swim meets and soccer games. Mark signed up to coach all the kids’ teams. He didn’t want to miss a moment with them. We had three children. Jeffrey was our oldest, then Kevin, then Melanie. Jeffrey was a leader like his Daddy. He wanted to build things. He erected tents in the living room. He slept in a sleeping bag. But Kevin was different. He was the tenderhearted one. He felt the pain of the world. I remember how shocked he was when he learned about slavery in school. He couldn’t even eat when he learned about the Holocaust. Jeffrey would always say: ‘Kevin! Stop thinking so much! Let’s go play soccer!’ But Kevin always felt like he had to figure out the world. He was our smart one. He wanted to be a doctor. He got two scholarships to college. He was the top cadet in ROTC. I knew that Kevin struggled with sadness. But I just gave him a bunch of Mom advice: ‘exercise more, ‘sleep more,’ ‘eat more vegetables.’ I tried to pray it away. I wrote letters to God, asking to lift Kevin’s ‘spirit of depression.’ And we didn’t tell anyone. I thought: ‘He’s doing so well in school. Don’t rock the boat.’ We kept it a secret. So I think we share in what happened.”

“I lost my dad when I was eleven. So I know what it means to be sad. I just didn’t know that you could die from being too sad. Kevin called us the night before. He hadn’t been sleeping. He’d been up all night playing this game called Sim City, and he’d just beaten the game. He’d become a four star general or something, and his friends were so happy for him, but he sounded so sad. He said: ‘I did everything the world says is success, but it’s not all it’s cracked up to be.’ Then he quoted Henry David Thoreau-- that line about the masses living lives of quiet desperation. And he was crying. And I said: ‘Kevin, I’m so proud of you. I’d be proud of you even if you were digging ditches. If it’s the Army, drop out. I’ll pay back the scholarships.’ But he told me: ‘Dad, I can’t quit. It’s the soldier’s creed.’ So I just told him that I loved him. And that was the last time we spoke. We got a call the next night from Jeffrey. They were living together at the time. Jeffrey was hysterical. He said: ‘Dad. Kevin’s gone!’ I said: ‘What do you mean? Gone?’ And he said: ‘Kevin’s dead! He hung himself!’ And I just started screaming: ‘No! No! No!’ And I told Carol what happened. And she wasn’t crying. I remember feeling scared that she wasn’t crying. She just fell on the floor and started crawling to the living room. She was trying to get to her Bible.”

“Jeffrey was set to deploy not long after Kevin’s death. I begged him not to go. I remember we went on a walk, and he said to me, in this real mature voice: ‘Dad, you know I have to go. My men need me.’ And I said: ‘Jeff. You don’t have to go. We need you here. Mom needs you, Melanie needs you, and I need you.’ But he insisted. I was a colonel at the time. And even though the father in me couldn’t understand, the soldier in me did. Jeffrey had to make his own path. He left for Iraq on Kevin’s birthday—November 15th, 2003. He was killed three months later. On that morning my boss was scheduled to leave on a trip. He was a two star general. We spent the morning together, then he told me ‘goodbye,’ and I assumed he left for the airport. But a few minutes later, I stepped into his office, and I found him standing alone in the dark. I said: ‘Sir, did you miss your plane?’ And he started walking toward me. And I knew. I knew when he took that first step. And he grabbed me, and he said: ‘Mark, it’s Jeff.’ And I said: ‘Is he hurt?’ And he told me: ‘Mark, he’s gone.’ And I said: ‘Are you sure?’ And he said: ‘I’ve known all morning. I verified three times.’ I thought ‘No, no, no, no, no. This can’t be. This isn’t possible. Not both of them.’”

“I knew the moment Mark came home. The general was with him. That morning I’d seen on the Internet that two soldiers were killed in Iraq. I immediately walked into the bathroom, and Mark was shaving, and I asked him if he thought it could be Jeff. He told me: ‘No way. We’d know by now.’ So when Mark came back home a few hours later, I knew. I started finding pictures of the boys together, and spreading them out on the table. I kept thinking: ‘The boys are together, the boys are together, the boys are together.’ I think I freaked out General Valcourt. He probably thought I was crazy. But saying those words was the only thing holding me together. The boys had always been so close. They were best friends as well as brothers. They did everything together. They even joked that they’d build their houses together, and share a pool, and share a dog. After Kevin’s death, Jeffrey always told me: ‘Don’t worry Mom. He’s with me. I can feel it.’ All of us kept journals when Kevin died. The grief counselor recommended it. But Jeffrey was the only one who kept it up. He addressed every entry to Kevin. They shipped us Jeffrey’s journal when he died, and the last thing he’d written was: ‘I’ll be in touch.’”

“We like to say that God has a plan, but we just didn’t get to have a say in it. After the boys died, we dedicated our lives to encouraging young people to get help with depression. So many soldiers are afraid to seek help. They’re afraid to tell the Army. They’re afraid of what their fellow soldiers will think. We want them to know that it’s no different than asking for help with a broken arm. After the boys died, we never thought we’d be happy again. Carol felt suicidal herself. I felt guilty for even laughing. But happiness returned slowly. Our daughter Melanie is doing great. She’s a runner, and a swimmer, and a nurse. I ended up getting promoted to general on September 22nd—Jeffrey’s birthday. My boss engraved my sons’ names on each star. During the ceremony, while he was pinning the stars on my shoulders, he told me: ‘Kevin and Jeffrey will always be with you.’ When I became a general, I was allowed to select an aide. I interviewed eight people for the position. I chose a fantastic young man named Joe Quinn. And Joe is now my son-in-law. He ended up falling in love with Melanie, they got married, and we’re expecting our first grandchild in a month. We are just giddy about that. So ‘happy now’ is different than ‘happy then,’ but we do feel happiness again. ‘Happy now’ is Melanie and Joe. ‘Happy now’ is our future grandchild. And ‘happy now’ is a young soldier who hears Kevin’s story, and tells us that they got help.”